|

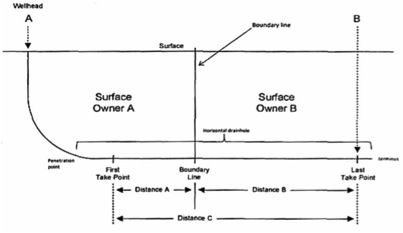

On December 20, 2013, the San Antonio Court of Appeals ruled on a dispute concerning the allocation of royalties from a horizontal well located on a landowner’s surface and sub-surface property and his neighbor’s sub-surface property. The landowner, Springer Ranch, Ltd, sought a declaratory judgment against their neighbor, Rosalie Sullivan. Springer Ranch argued that a 1993 contract entitled them to receive all royalties from the horizontal well situated on the surface of their property. Before addressing the specific terms of the contract, it is important to understand the origin of these two parties’ interests. Springer Ranch and Sullivan are heirs or successors-in interest to Alice Burkholder. Mrs. Burkholder owned 8,545 acres of land in La Salle and Webb County, Texas. Upon her death, she bequeathed the property to her husband Joseph for life. When Joseph died in 1990, Mrs. Burkholder’s Will partitioned the property into three separate tracts and devised the 1st tract to Barbara Springer (Springer Ranch), the 2nd tract to Rosalie Sullivan, and the 3rd tract to various other owners who entered into a partition agreement. In 1956, Mrs. Burkholder executed an oil and gas lease on the entire property which is still in full force and effect today. This lease is the main cause of royalty ownership uncertainty between Springer Ranch and Sullivan. In response to this uncertainty of royalty ownership, Springer Ranch and Sullivan entered into a contract agreement in 1993. The relevant provision is as follows: "the parties contract and agree with each of the other parties, that all royalties payable under the above described Oil and Gas Lease from any well or wells on said 8,545.02 acre tract, shall be paid to the owner of the surface estate on which such well or wells are situated, without reference to any production unit on which such well or wells are located….." At the time this agreement was made, it affected six vertical wells, and for almost 20 years, the contract worked appropriately. However, the implementation of a horizontal well on the Springer Ranch property (“the SR2 well”) began to cause problems. The SR2 well is situated on the surface of the Springer Ranch property, delves into the sub-surface of Springer Ranch, and once underground, crosses the Springer Ranch-Sullivan property line. When Sullivan became aware that the SR2 well was extracting oil and gas directly beneath their property, they attempted to negotiate with Springer Ranch for a share in the royalty payments. After Springer Ranch denied this request, Sullivan demanded royalty payments from the well operator. The well operator refused to make royalty payments to either party until the conflict was resolved. The following is an illustration of Springer Ranch’s SR2 well. Springer Ranch then sued Sullivan, seeking a declaration that they were entitled to 100% of royalty payments according to the 1993 contract. Springer Ranch interpreted the contract to mean that whoever owned the “surface estate” with a well on it was entitled to all the royalty payments from that well, regardless of the acreage that could reasonably be considered productive of oil and gas.

Sullivan in turn requested that the trial court allocate the royalties of the SR2 well between Springer Ranch and Sullivan based on the location of the productive portions of the well. Sullivan’s argument was based on the interpretation of the term “surface estate” in the 1993 contract. Sullivan claimed that the SR2 well was “situated” on their property since it crossed the property boundary underground. After considering both parties arguments, the trial court held that: (I) The June 3, 1993 agreement referred to by the parties as the “Royalty Agreement,” concerning ownership of royalties under the 1956 oil and gas lease is unambiguous. (II) The Royalty Agreement requires that the royalties from the SR2 well be divided between Sullivan and Springer Ranch based on the productive portions of the well situated on their properties. (III) Sullivan is entitled to receive royalty of .08500689 of production from the SR2 well and Springer Ranch is entitled to receive royalty of .03999311 of production from the SR2 well. (IV) Royalties from any future horizontal wells that are subject to the Royalty Agreement and that are situated on more than one tract of land and owned by any of the parties to this suit or their heirs, successors, and assigns will be allocated in proportion to the producing portions of the well situated on each of the respective tracts. Springer Ranch appealed this judgment. The Court of Appeals first considered the contract between Springer Ranch and Sullivan. The Court of Appeals stated that “when interpreting a contract, the primary concern is to ascertain the true intentions of each party in the agreement. Furthermore, these intentions should be considered in light of the circumstances surrounding the contract’s execution.” The objective of the 1993 contract was to resolve existing discrepancies between the division of the original Burkholder property and the division of its mineral interests. Between the oil and gas lease’s execution in 1956 and Joseph’s death, the original lessee-operator carved out portions of its mineral interest under the Burkholder lease and assigned those interests to other operators, who in turn subdivided and assigned their interests to other operators. When Springer Ranch and Sullivan’s remainder interests in the land vested in 1990, their property boundary lines did not match the boundary lines of the mineral interest holders. To solve this problem, the parties agreed that each property owner would receive all the royalties from the wells “situated on” their “surface estate” and would forego any claims to the royalties from wells on the adjoining parties’ surface estates. The Court of Appeals then addressed the contract’s text. What is a “well”? Sullivan argues that “well” should be understood as “the entire underground orifice from which oil and gas are produced.” Springer Ranch claims that a “well” is meant to be “only the topmost portion of the hole on the surface where hydrocarbons exit the earth or the structure overlying the well.” The Court of Appeals examines the definition of a “well” from four separate dictionaries and consulted a petroleum engineer to conclude that Sullivan’s definition is correct. Springer Ranch was advocating that the Court apply the definition of “wellhead” to “well” which was improper. What is a “surface estate”? According to the Court’s interpretation, the term “surface estate” was meant to describe “portions of the earth, over which the surface estate owner holds dominion after a severance of the mineral estate.” When a surface owner conveys his mineral rights to another, the surface of the leased lands and everything in such lands still belongs to the landowner, except for the oil and gas deposits covered by the lease. This ownership includes geological structures beneath the surface. Therefore, the holder of a mineral estate has the right to exploit minerals, but does not own the subsurface mass. Using this rationale, the Court of Appeals held that that SR2 well was “situated” on one or more “surface estate.” Even though the SR2 well was technically below the surface of Sullivan’s property, the SR2 well was still “situated” on Sullivan’s “surface estate” because Sullivan owned the subsurface materials around the well. Therefore, to be consistent with the contract, the royalties from the SR2 well should be allocated between Springer Ranch and Sullivan. Springer Ranch’s main argument on appeal was that the contract provision “without reference to any production unit on which such well or wells are located,” barred any division or allocation of royalties between adjacent parties. In the alternative, Springer Ranch contended that royalties should be allocated on the basis of the entire length of the well “on” the parties’ property and not just the productive portions. The Court of Appeals disagreed with Springer Ranch, stating that ‘the calculation for royalties should not be based on the whole length of a well because production is not obtained from the whole length of a well. Rather, production is obtained from various take-points throughout the well. Therefore, the allocation of royalties should be proportional with the productive portions of the SR2 beneath BOTH properties. The proportions described above were calculated by Sullivan’s expert. The expert measured the total distance between the SR2 well’s first and last take-points, the distance between its first take-point and the property line between Sullivan and Springer Ranch’s properties, and the distance between the property line and the well’s last take-point. The expert multiplied the 1/8 royalty provided under the 1956 lease by the ratio of the total distance between the first and last take-points to allocate the royalties. He calculated: Sullivan’s net revenue interest in the well based on the one-eighth lease royalty would be 0.08500689 (2,615.9/3,846.6 x 1/8) and Springer Ranch’s share would be 0.03999311 (1,230.7/3, 846.6x 1/8).” Springer Ranch did not dispute these measurements or calculations. Based on these calculations, the Court of Appeals determined that there was summary judgment evidence to support the trial court’s judgment allocating all royalties payable from the SR2 well based on the productive portions of the well situated on each of the two properties. Furthermore, the Court held that this same calculation of royalties would apply to future horizontal wells on any of the parties’ properties.

2 Comments

6/2/2016 07:20:29 am

Thanks so much for this article. It has provided a great example of the need for take point allocation of royalties, when the origin of this type of royalty allocation has been difficult to find.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Oil and Gas Law Blog

Brandon M. Barchus Archives

June 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed