|

The issue in this case is whether the term “cost-free” in the overriding royalty provision in the lease between Chesapeake Exploration (hereinafter referred to as “Chesapeake”) and Martha Rowan Hyder, Brent Rowan Hyder, and Whitney Hyder More (hereinafter referred to as the “Hyders”) suggests that the overriding royalty is free of postproduction costs.

The Hyder family leased 948 mineral acres in the Barnett Shale to Chesapeake Exploration. The lease contained three royalty provisions. One provision was for 25% of the market value at the well of all oil and other liquid hydrocarbons, however no oil was produced from the lease. Another royalty provision was for 25% of the price actually received by Lessee for all gas produced from the leased premises and sold or used. The lease stated that the royalty was expressly free and clear of all production and postproduction costs and expenses, and additionally listed examples of various expenses. The third royalty provision, and the one in dispute, called for a “perpetual, cost-free (except only its portion of production taxes) overriding royalty of 5.0% of gross production obtained from directional wells drilled on the lease but bottomed on nearby land.” The lease contained two other provisions. One was the disclaimer that the Lessors and Lessee agree that the holding in the case of Heritage Resources, Inc. v. NationsBank, 939 S.W. 2d 118 (Tex. 1996) would have no application to the terms and provisions of this Lease. The other was that each Lessor had the continuing right and option to take its royalty share in kind. Chesapeake sold all the gas produced to an affiliate, Chesapeake Energy Marketing, Inc. (“Marketing”), which then gathered and transported the gas through both affiliated and interstate pipelines for sale to third-party purchasers in distant markets. Marketing paid Chesapeake a “gas purchase price” for volumes determined at the wellhead or at the terminus of Marketing’s gathering system. The gas purchase price is calculated based on a weighted average of the third-party sales prices received minus postproduction costs. The overriding royalty Chesapeake paid the Hyders was 5% of the gas purchase price and the Hyders contend that their overriding royalty should be based on the gas sales price, which does not deduct postproduction costs. The Hyders argue that the requirement that the overriding royalty be “cost-free” can only refer to postproduction costs, since a royalty by nature is already free of production costs. However, Chesapeake argues that “cost-free overriding royalty” is just a synonym for overriding royalty and cannot refer to postproduction costs. Generally, an overriding royalty on oil and gas production is free of production costs but must bear its share of postproduction costs unless the parties modify the general rule by agreement. By express provisions, parties may agree to effectively exclude post-production costs, notwithstanding industry custom that royalties are subject to these costs. The term “cost-free” in this overriding royalty provision includes post-production costs. The Supreme Court disagreed with the Hyders in that “cost-free” in the Hyder-Chesapeake overriding royalty provision could not refer to production costs. However, Chesapeake still must show that while the general term “cost-free” does not distinguish between production and postproduction costs and basically refers to all costs, it nevertheless cannot refer to postproduction costs. Chesapeake argued that the gas royalty provision showed that when the parties wanted a postproduction cost-free royalty, they were much more specific in the provision. However, the Court found that the additional detail in the gas royalty provision only emphasized its cost-free nature and had no effect on the meaning of the provision and thus, the simple “cost-free” requirement of the overriding royalty achieved the same end. The overriding royalty provision stated that the overriding royalty was to be cost-free except as to taxes nothing more was needed to accomplish the intent to adequately convey an interest free of both production and postproduction costs. Additionally, Chesapeake argued that because the overriding royalty is paid on “gross production”, the reference is to production at the wellhead, making the royalty tantamount to one based on the market value of production at the wellhead, which includes postproduction costs. However, it is not disputed that the overriding royalty may be paid in cash and not in kind, even though the Hyders retained the right to take it in kind. Stipulating that the volume on which a royalty is due must be determined at the wellhead says nothing about whether the overriding royalty must bear postproduction costs. If the Hyders were to take their overriding royalty in kind, they have the option to use the gas on the property, transport it themselves to a buyer, or pay a third party to transport the gas to market in which they may or may not incur postproduction costs. According to the lease, the choice of how to take their royalty, and the consequences, were left to the Hyders. Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that “cost-free” in the overriding royalty provision includes postproduction costs. Conclusion: The Supreme Court ruled that the overriding royalty provision that called for a perpetual, cost-free (except only its portion of production taxes) overriding royalty of 5.0% of gross production obtained from directional wells drilled on the lease but bottomed on nearby land freed the overriding royalty of postproduction costs. Although an overriding royalty on oil and gas production must bear postproduction costs, the overriding royalty can be free and clear of all postproduction costs and expenses if the parties’ lease expressly states otherwise. The Supreme Court determined that the term “cost-free” in this lease meant to include postproduction expenses. On June 27, 2014, the Supreme Court of Texas made an important decision that will effect future oil and gas royalty payments. The decision was based on a dispute between a royalty owner and working interest owner of two oil and gas leases in Kent County, Texas. The basis of the dispute was whether the royalty owners were required to share in the cost of removing CO2 from casinghead gas produced through a well.

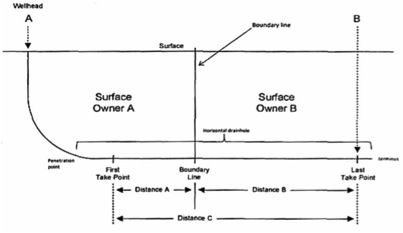

“French,” owned royalty interests under two oil and gas leases still being held by production since the late 1940’s by Occidental Permian Ltd. (“Oxy.”) The first lease granted French a royalty “on gas, including casinghead gas or other gaseous substance produced from said land and sold or used off the premises or in the manufacture of gasoline or other product therefrom equal to the market value at the well of one-eighth (1/8th) of the gas so sold or used.” The second lease called for a royalty of “1/4 of the net proceeds from the sale of gasoline or other products manufactured and sold from casinghead gas after deducting the cost of manufacturing the same.” The term “royalty” as used in oil and gas leases, is generally considered free of the expenses of production but subject to postproduction costs. In other words, a royalty interest owner will not have to pay for the cost of extracting oil from the land, but will have to pay for the cost of treating the oil to make it marketable. This separation of payment responsibilities was the central issue between French and Oxy. In 1954, the two leases were pooled together to form one unit in order to increase the recovery of oil. French and Oxy entered into a Unitization Agreement in which French consented to the injection of extraneous substances into the oil reservoir and gave Oxy discretion in determining “whether and how to conduct these operations.” This secondary recovery operation involved injecting water into the reservoir to increase and maintain pressure lost through primary production and to sweep oil toward producing wells. The operation was very successful. The wells produced a total of more than 270 million barrels of oil and billions of cubic feet of casinghead gas. By the late 1990s, water flooding had become less effective and oil production had declined from 30,000 barrels per day to about 1,500 barrels per day. This decline in production forced Oxy to search for other alternative methods of recovery. Oxy decided that injecting CO2 into the reservoir was the best viable option. CO2 injection is similar to water injection in that both methods are designed to increase pressure and push oil and gas towards the wells. However, CO2 flooding is much more expensive than water flooding. Separating oil from water is a relatively simple operation. The oil and water mixture is placed in a large storage tank and the oil floats to the top of the tank. French was never charged by Oxy for this operation. Oxy treated the separation of oil from water as a part of production. Separating casinghead gas from CO2 is much more complicated. The CO2 flooding method resulted in the extraction of gas that was 85% CO2. Therefore, Oxy was unable to perform the complicated separation process. Oxy contracted with Kinder Morgan to build a plant that could process CO2 concentrated gas. Kinder Morgan then contracted with Torch Energy Marketing to further process the gas. In response to the method of CO2/casinghead gas separation chosen by Oxy, French sued Oxy for underpaying royalties since the beginning of the CO2 flood. French contended that Oxy’s CO2 separation method was a part of production and was supposed to be paid only by Oxy. At the District Court level, the trial court agreed with French and awarded them $10,074,262.33 in underpaid royalties. The Court of Appeals reversed the District Court’s decision due to discrepancies in the calculation of damages. The Court of Appeals did not address the question of whether the cost of separating CO2 from casinghead gas was a production or post production expense. The Supreme Court of Texas did address this important issue. Upon review, the Supreme Court of Texas looked to the original leases between French and Oxy. The first lease provided for a royalty on casinghead gas based on its market value at the well. French argued that these royalties should be based only on the value of the non-CO2 gas, the “native” gas, at the well, which could be determined by deducting only the processing costs unrelated to the removal of CO2 from the value of the final products. The second lease provided for a royalty based on the sales proceeds of casinghead gas products net of the cost of manufacturing them. French argued that that cost does not include the expense of removing CO2 from the gas. French claimed that the removal of CO2 for reinjection was a part of production, the expense of which was to be born solely by Oxy. Oxy argued that for both leases, the cost of removing CO2 was a postproduction expense involved in extracting the NGLs (Natural Gas Liquids) that must be deducted from their market price in determining royalties. French argued further that the process of separating CO2 from casinghead gas and the process of separating water from oil were the same. Oxy had always treated oil and water separation as a part of production, charging no part of the expense to French. Therefore, according to French, gas processing should be treated the same way. The Supreme Court disagreed, determining that oil and water are immiscible, and separating them is a relatively simple process compared to separating CO2 from gas, which requires special technology. Furthermore, separating water from oil is essential to continued economic production. The result of water flooding, which is critical to recovering the oil from the ground, is that an enormous amount of water is produced with the oil, more than 23 barrels of water to one barrel of oil. Separating the water is not only for reinjection into the reservoir; it is necessary to make the oil marketable. Without water flooding and the subsequent separation of oil and water, oil production would not be viable. The CO2 flood is also critical to continued oil production and the result is that the casinghead gas is more than 85% CO2. But separating CO2 from casinghead gas is not necessary for the continued production of oil, which was the purpose of both the water flood and separation. Gas processing is certainly economically beneficial to French and Oxy, but gas processing is not essential to the operation of the field as the water and oil processing is. The Supreme Court of Texas further states that “Not only is it unnecessary for continued oil production to separate the CO2 from the casinghead gas, Oxy has no obligation to do so.” Under the Unitization Agreement, Oxy had the right to re-inject the entire production of casinghead gas back into the reservoir, and Oxy considered that option. If Oxy decided to do so, French would not be entitled to any royalty on the casinghead gas. Instead, Oxy decided to process the gas to obtain a more concentrated stream of CO2 for reinjection and to extract the NGLs to be marketed. Therefore, the Supreme Court of Texas decided that CO2 removal was in fact a postproduction expense and since French gave Oxy the right and discretion to decide whether or not re-inject or process the casinghead gas, they must share in the cost of CO2 removal. On December 20, 2013, the San Antonio Court of Appeals ruled on a dispute concerning the allocation of royalties from a horizontal well located on a landowner’s surface and sub-surface property and his neighbor’s sub-surface property. The landowner, Springer Ranch, Ltd, sought a declaratory judgment against their neighbor, Rosalie Sullivan. Springer Ranch argued that a 1993 contract entitled them to receive all royalties from the horizontal well situated on the surface of their property. Before addressing the specific terms of the contract, it is important to understand the origin of these two parties’ interests. Springer Ranch and Sullivan are heirs or successors-in interest to Alice Burkholder. Mrs. Burkholder owned 8,545 acres of land in La Salle and Webb County, Texas. Upon her death, she bequeathed the property to her husband Joseph for life. When Joseph died in 1990, Mrs. Burkholder’s Will partitioned the property into three separate tracts and devised the 1st tract to Barbara Springer (Springer Ranch), the 2nd tract to Rosalie Sullivan, and the 3rd tract to various other owners who entered into a partition agreement. In 1956, Mrs. Burkholder executed an oil and gas lease on the entire property which is still in full force and effect today. This lease is the main cause of royalty ownership uncertainty between Springer Ranch and Sullivan. In response to this uncertainty of royalty ownership, Springer Ranch and Sullivan entered into a contract agreement in 1993. The relevant provision is as follows: "the parties contract and agree with each of the other parties, that all royalties payable under the above described Oil and Gas Lease from any well or wells on said 8,545.02 acre tract, shall be paid to the owner of the surface estate on which such well or wells are situated, without reference to any production unit on which such well or wells are located….." At the time this agreement was made, it affected six vertical wells, and for almost 20 years, the contract worked appropriately. However, the implementation of a horizontal well on the Springer Ranch property (“the SR2 well”) began to cause problems. The SR2 well is situated on the surface of the Springer Ranch property, delves into the sub-surface of Springer Ranch, and once underground, crosses the Springer Ranch-Sullivan property line. When Sullivan became aware that the SR2 well was extracting oil and gas directly beneath their property, they attempted to negotiate with Springer Ranch for a share in the royalty payments. After Springer Ranch denied this request, Sullivan demanded royalty payments from the well operator. The well operator refused to make royalty payments to either party until the conflict was resolved. The following is an illustration of Springer Ranch’s SR2 well. Springer Ranch then sued Sullivan, seeking a declaration that they were entitled to 100% of royalty payments according to the 1993 contract. Springer Ranch interpreted the contract to mean that whoever owned the “surface estate” with a well on it was entitled to all the royalty payments from that well, regardless of the acreage that could reasonably be considered productive of oil and gas.

Sullivan in turn requested that the trial court allocate the royalties of the SR2 well between Springer Ranch and Sullivan based on the location of the productive portions of the well. Sullivan’s argument was based on the interpretation of the term “surface estate” in the 1993 contract. Sullivan claimed that the SR2 well was “situated” on their property since it crossed the property boundary underground. After considering both parties arguments, the trial court held that: (I) The June 3, 1993 agreement referred to by the parties as the “Royalty Agreement,” concerning ownership of royalties under the 1956 oil and gas lease is unambiguous. (II) The Royalty Agreement requires that the royalties from the SR2 well be divided between Sullivan and Springer Ranch based on the productive portions of the well situated on their properties. (III) Sullivan is entitled to receive royalty of .08500689 of production from the SR2 well and Springer Ranch is entitled to receive royalty of .03999311 of production from the SR2 well. (IV) Royalties from any future horizontal wells that are subject to the Royalty Agreement and that are situated on more than one tract of land and owned by any of the parties to this suit or their heirs, successors, and assigns will be allocated in proportion to the producing portions of the well situated on each of the respective tracts. Springer Ranch appealed this judgment. The Court of Appeals first considered the contract between Springer Ranch and Sullivan. The Court of Appeals stated that “when interpreting a contract, the primary concern is to ascertain the true intentions of each party in the agreement. Furthermore, these intentions should be considered in light of the circumstances surrounding the contract’s execution.” The objective of the 1993 contract was to resolve existing discrepancies between the division of the original Burkholder property and the division of its mineral interests. Between the oil and gas lease’s execution in 1956 and Joseph’s death, the original lessee-operator carved out portions of its mineral interest under the Burkholder lease and assigned those interests to other operators, who in turn subdivided and assigned their interests to other operators. When Springer Ranch and Sullivan’s remainder interests in the land vested in 1990, their property boundary lines did not match the boundary lines of the mineral interest holders. To solve this problem, the parties agreed that each property owner would receive all the royalties from the wells “situated on” their “surface estate” and would forego any claims to the royalties from wells on the adjoining parties’ surface estates. The Court of Appeals then addressed the contract’s text. What is a “well”? Sullivan argues that “well” should be understood as “the entire underground orifice from which oil and gas are produced.” Springer Ranch claims that a “well” is meant to be “only the topmost portion of the hole on the surface where hydrocarbons exit the earth or the structure overlying the well.” The Court of Appeals examines the definition of a “well” from four separate dictionaries and consulted a petroleum engineer to conclude that Sullivan’s definition is correct. Springer Ranch was advocating that the Court apply the definition of “wellhead” to “well” which was improper. What is a “surface estate”? According to the Court’s interpretation, the term “surface estate” was meant to describe “portions of the earth, over which the surface estate owner holds dominion after a severance of the mineral estate.” When a surface owner conveys his mineral rights to another, the surface of the leased lands and everything in such lands still belongs to the landowner, except for the oil and gas deposits covered by the lease. This ownership includes geological structures beneath the surface. Therefore, the holder of a mineral estate has the right to exploit minerals, but does not own the subsurface mass. Using this rationale, the Court of Appeals held that that SR2 well was “situated” on one or more “surface estate.” Even though the SR2 well was technically below the surface of Sullivan’s property, the SR2 well was still “situated” on Sullivan’s “surface estate” because Sullivan owned the subsurface materials around the well. Therefore, to be consistent with the contract, the royalties from the SR2 well should be allocated between Springer Ranch and Sullivan. Springer Ranch’s main argument on appeal was that the contract provision “without reference to any production unit on which such well or wells are located,” barred any division or allocation of royalties between adjacent parties. In the alternative, Springer Ranch contended that royalties should be allocated on the basis of the entire length of the well “on” the parties’ property and not just the productive portions. The Court of Appeals disagreed with Springer Ranch, stating that ‘the calculation for royalties should not be based on the whole length of a well because production is not obtained from the whole length of a well. Rather, production is obtained from various take-points throughout the well. Therefore, the allocation of royalties should be proportional with the productive portions of the SR2 beneath BOTH properties. The proportions described above were calculated by Sullivan’s expert. The expert measured the total distance between the SR2 well’s first and last take-points, the distance between its first take-point and the property line between Sullivan and Springer Ranch’s properties, and the distance between the property line and the well’s last take-point. The expert multiplied the 1/8 royalty provided under the 1956 lease by the ratio of the total distance between the first and last take-points to allocate the royalties. He calculated: Sullivan’s net revenue interest in the well based on the one-eighth lease royalty would be 0.08500689 (2,615.9/3,846.6 x 1/8) and Springer Ranch’s share would be 0.03999311 (1,230.7/3, 846.6x 1/8).” Springer Ranch did not dispute these measurements or calculations. Based on these calculations, the Court of Appeals determined that there was summary judgment evidence to support the trial court’s judgment allocating all royalties payable from the SR2 well based on the productive portions of the well situated on each of the two properties. Furthermore, the Court held that this same calculation of royalties would apply to future horizontal wells on any of the parties’ properties. Flip-Flop of Attorneys' Fee Awards in Lease Acquisition and Participation Agreement Lawsuit6/16/2014 On May 22, 2014, the Texas Court of Appeals in Waco ruled on a breach of contract claim stemming from an oil and gas venture between two oil and gas companies. The appellant, Fleet Oil & Gas, and appellee, EOG Resources entered into a Lease Acquisition and Participation Agreement in May of 2007. The agreement contained two sections. The first section, the lease acquisition, is as follows: Fleet desires to sell and EOG wishes to purchase all of Fleet’s right, title and interest in 100% of certain oil and gas and mineral rights leases in Johnson County, Texas. EOG will pay $3,500 per net leasehold acre, resulting in an initial purchase price payment of $1,736,845.00. EOG currently owns 108.690 net acres out of the Hendricks Survey and Fleet owns 495.670 net acres out of the same survey.

The parties additionally executed a joint operating agreement (JOA) in conjunction with the second section, the participation agreement. This agreement outlined the terms for extracting oil and gas from the contract area and the interests of the parties in respect to the contract area. The agreement states that “Regardless of the record title ownership of the leases within the contract area, EOG shall own 75% working interest, and Fleet shall own 25% working interest.” The trial court interpreted this clause to mean that Fleet is entitled to 25% working interest to all of EOG’s leases within the contract area, including the 108.690 net acres EOG already owned. It is likely that EOG only meant to give Fleet 25% working interest on the 495.670 net acres conveyed by Fleet to EOG. However, the written agreement does not illustrate that intention. Therefore, according to the agreement, Fleet is entitled to 25% working interest in all of EOG’s leases in the Contract Area, being the entire 604.36 net acres. In addition to the participation of the working interest, EOG agreed to: (1) commence actual drilling operations on not fewer than 3 wells on the contract area before November 15, 2007, and “diligently prosecute the drilling, completion and sale of gas from such wells; and to drill, frac, equip, complete, and deliver gas to initial sales from at least 12 wells, and to commence actual drilling operations on at least 2 additional wells.” In the event that EOG fails to adhere to the drilling operations stated above, Fleet’s working interest shall increase from 25% to 30%, and EOG’s working interest shall be reduced from 75% to 70%. On February 12, 2008, Fleet sent a letter to EOG claiming that EOG was in default under the drilling operations clause of the lease because EOG had failed to “diligently prosecute the drilling, completion and sale of gas” from the 3 initial wells they had drilled. Therefore, Fleet contended that they were entitled to a 5% increase in their working interest. At trial, Fleet sought a declaratory judgment that EOG was required to diligently prosecute the drilling, completion, and sale of gas from the 3 initial wells and that its failure to do so resulted in an increase in Fleet's working interest from 25% to 30%. Additionally, Fleet sought declaratory judgment that it had a 25% working interest in all the EOG leases in the contract area, and EOG could only deduct the actual royalty burden from revenue attributable to Fleet’s working interest in EOG leases. Therefore, Fleet brought a claim for breach of contract resulting from EOG’s failure to pay them 25% working interest in the entirety of the Contract Area. In response to Fleet’s arguments, EOG sought a declaratory judgment that under the agreement, they did in fact commence actual drilling operations on no fewer than 3 wells before November 15, 2007, and did diligently prosecute the drilling, completion, and sale of gas from these wells. Therefore, the two parties’ working interests remained the same and Fleet was not entitled to a 5% working interest increase. EOG also sought damages in the form of attorney’s fees. The trial court submitted two issues, the “diligence issue” and the “working interest issue.” For the diligence issue, the jury ruled in favor of EOG, stating that EOG did not fail to diligently prosecute the completion and sale of gas from the initial 3 wells. On the working interest issue, the jury found for Fleet, finding that Fleet and EOG did agree that Fleet would own a 25% working interest, subject only to actual burdens, over the entire Contract Area. The trial court concluded that EOG was the “prevailing party” in the dispute, and were entitled to recover the cost of attorney’s fees from Fleet. Fleet was not awarded attorney fees, and appealed this ruling. On appeal, Fleet argued that EOG was not entitled to attorney’s fees. The appellate court agreed with Fleet, and ruled that “to recover attorney’s fees in Texas, a party must (1) prevail on a cause of action for which attorney’s fees are recoverable, and (2) recover damages.” A party who defends against a plaintiff’s claim but presents no breach of contract claim themselves is not entitled to recover attorney’s fees. EOG did not “prevail on a cause of action” in this matter. Rather, they successfully defended against Fleet’s cause of action. Furthermore, EOG did not recover any damages in the litigation. Because EOG failed to satisfy either of the two elements listed above, the Court of Appeals ruled that that EOG was not entitled to an award of attorney’s fees from Fleet. Fleet additionally claimed that they were entitled to the award of attorney’s fees which the trial court refused. Using the same elements listed above to qualify for attorney’s fees, the appellate court ruled that Fleet was entitled to attorney’s fees because Fleet “prevailed on a cause of action for which attorney’s fees are recoverable, Fleet’s breach of contract claim resulting from EOG’s failure to pay them 25% working interest in the Contract Area. Fleet also satisfied the second element since they “recovered damages” in the stipulated amount of money which EOG failed to pay them of the entire 25% working interest. Thus, the end result was a flip-flop of the attorney’s fee awards, resulting in an additional net loss to EOG of approximately $700,000. Sometime in the near future, the Supreme Court of Texas will make an important decision regarding whether a party can recover stigma damages to their property, even when the physical damage to their property was not permanent. The opportunity to rule on this issue came before the Court through consecutive appeals where a property owner alleged that his land was contaminated due to the negligence of a neighboring Metal Processing company. The landowner in this matter is Mel Acres Ranch and the Metal Company is Houston Unlimited, Inc. Metal Processing (HUI).

HUI and Mel Acres Ranch are located in Washington County, Texas. The Mel Acres property is undeveloped ranchland located across Highway 290 from HUI's facility. A culvert flows downhill from HUI's facility, under the highway, and into a stock tank “a large pond” on the Mel Acres property. Mel Acres also contains two background ponds, which are not hydraulically connected to HUI's property and are not affected by HUI's activities. In late 2007, the Mel Acres lessee complained that a number of their calves had died or experienced various defects. Additionally, HUI had been observed dumping the contents of a large drum into the culvert. In response to these problematic actions of HUI, Mel Acres retained an environmental consultant to test water samples on the property. These tests revealed arsenic, chromium, copper, nickel, and zinc exceeding state action levels in the culvert and copper exceeding state action levels in the large pond. After receiving the water test results, Mel Acres sued HUI for trespass, nuisance, and negligence. Mel Acres alleged that it suffered permanent damage, measured by loss in market value of the property. The trial court jury found that HUI did not create a permanent nuisance on the property or commit trespass. However, the jury did find that HUI's negligence proximately caused the occurrence or injury in question. On July 15, 2010, the trial court signed a final judgment awarding Mel Acres $349,312.50 in actual damages. HUI appealed the trial court’s judgment which found that Mel Acres was entitled to the recovery of stigma damages. In 2012, the Houston Court of Appeals affirmed the trial courts judgment in favor of Mel Acres Ranch. The issues on appeal were slightly different than the issue before the trial court. On appeal, the issue of negligence and causation were not contested by HUI. However, HUI contested the type of damage caused by their negligence. HUI argued that their negligent dumping of hazardous materials caused “temporary” rather than “permanent” damage to the Mel Acres Ranch. HUI additionally argued that “constituents on the plaintiff’s property must exceed state action levels” and cause permanent injury to the property in order for a plaintiff to successfully recover damages for environmental contamination. The Texas Court of Appeals disagreed, and held that Mel Acres successfully proved the permanent damage of diminished market value. This lost market value was caused by the “temporary” contamination of the Mel Acres property which in turn resulted in a “permanent” stigma.The Texas Court of Appeals additionally held that proof of physical property damage is not required to support a ruling for permanent property damage. Therefore, a plaintiff is entitled to the recovery of lost market value that results from a permanent stigma upon the land. This holding is the first of its kind in Texas and one of the main focus points for the Texas Supreme Court as they review this case. One of the first things considered by the Texas Supreme Court on review of this matter is the reasoning of the Texas Court of Appeals. The Texas Court of Appeals decided that a plaintiff could recover lost market value of a property that was temporarily damaged by the defendant but permanently stigmatized due to the damage. The Texas Court of Appeals made this ruling by observing other jurisdictions’ appoach to the same question. Utah and Pennyslvania courts have both addressed this same question. The general holding by these two courts is that a plaintiff can recover stigma damages when: (1) The defendant caused temporary physical injury to plaintiff’s land and; (2) Repair of this damage cannot return the value of the property to its prior level due to a lingering negative perception. The Texas Supreme Court may also have to rule on other issues pertinent to this case. Since the ruling of the Texas Court of Appeals was in favor of Mel Acres, the issues presented by HUI, the petitioner, are a good starting point for the analysis of what is being discussed behind the Texas Supreme Court doors. The arguments set forth to the Texas Supreme Court by HUI can be divided into four categories. The first argument deals with causation of permanent damages. The second argument addresses the validity of Mel Acre’s real estate expert’s testimony. The third requests that the Supreme Court adopt the Taco Cabana doctrine. Lastly, the fourth argument claims that there is no evidence of permanent injury. HUI first argues that in any claim based on a negligence theory, causation must be proven in order for a plaintiff to recover damages. HUI contends that Mel Acres cited no evidence where HUI, or even its expert, admitted that HUI’s negligence caused permanent injury to Mel Acres. HUI also argues that they submitted extensive evidence (including admissions produced from the Mel Acres experts) disproving that HUI caused permanent injury to the property and that Mel Acres made no attempt to analyze this evidence. Rather, according to HUI, Mel Acres is urging the Supreme Court to ignore its past decisions, and rely on a portion of the Pattern Jury Charge, to support the argument that Mel Acres did not need to prove that HUI’s negligence caused permanent injury. Lastly, HUI argues that Mel Acres failed to provide any credible support for the conclusion that HUI did not controvert that its negligence caused permanent injury and they contend that this failure calls for a reversal from the Supreme Court of Texas. The second argument presented by HUI claims that Mel Acre’s real-estate expert’s testimony is insufficient to support the Court of Appeal’s affirmation of judgment in favor of Mel Acres. HUI argues that Mel Acres makes no effort to defend what its real estate expert claimed to be comparable properties with a reduction in market value due to contamination. Justice Boyce of the Court of Appeals based his dissent along the same lines, stating that the properties selected by the Mel Acres expert bear small, insignificant similarities to the Mel Acres property. Mel Acres complains that HUI did not preserve its objection to the comparables upon which the real estate expert relied. In response to the Mel Acres complaint, HUI states that they did object to the comparables in a pre-trial motion to strike this very expert. Additionally, given the extensive record regarding the “comparables,” it is clear that neither Mel Acres nor their expert could supply any additional support for the use of these two “comparables,” according to HUI. HUI also points out that Mel Acres does not dispute that the property has contamination above the TCEQ state levels that cannot be linked to HUI in the “background ponds.” HUI claims that the Mel Acres real-estate expert made no attempt to separate what HUI might have caused from what HUI clearly did not cause and therefore this expert testimony cannot support a judgment under Texas law. HUI’s third argument for the Texas Supreme Court requests the adoption of the Taco Cabana Doctrine. In Taco Cabana, the court held that a gas-station lessee was not liable to lessor for contamination of property in unreasonable levels because the State provided a closure letter stating that any constituents caused by a leak in lessee's storage tank had been corrected below actionable levels. Taco Cabana was a negligence case, where the levels at the property in question were temporarily over the state action levels. Taco Cabana’s holding means that once the levels are back down below the state action levels, any common law duties are displaced. HUI asserts that both Mel Acres and the Court of Appeals tried to avoid admitting that the decision of the Court of Appeals conflicts with the holding in Taco Cabana. Because of this avoidance, HUI claims that as a matter of sound jurisprudence and good public policy, the Supreme Court of Texas Court should affirm the holding in Taco Cabana and apply it to this matter. If so, the Supreme Court would likely reverse and render the court of appeals previous ruling in favor of HUI. HUI’s final argument is that the damage done the Mel Acres property was temporary rather than permanent. This contention is based on the fact that Mel Acres did not dispute that its environmental experts had no opinion as to what the concentration of alleged contamination would have been on the day of trial, or on any day after trial. HUI states that when any future impact would be so highly speculative, the Supreme Court of Texas has said that the injury must be temporary. HUI urges the Court to reverse and render judgment in their favor due to the lack of certainty that future damages to the Mel Acres property would be permanent. Regarding this issue, the Supreme Court will be tasked with the duty to decide whether or not Mel Acres can recover for a permanent stigma resulting from a temporary physical contamination. Anytime a dispute reaches the Supreme Court of Texas, its resolution has the potential to greatly affect the interests of the citizens of the State of Texas. This dispute between HUI and Mel Acres is important because its resolution will undoubtedly have a substantial effect on environmental law and damage recovery in Texas. Let’s assume that the Supreme Court of Texas rules in favor of HUI, meaning that any individual or company who temporarily contaminates another person’s property will not be responsible for permanent stigma damages so long as they clean the property after. How does this apply in the real world? Is it realistic to expect potential property buyers to disregard contamination and pay full market value for what was once contaminated property? A great illustration of the perception of contamination comes from an episode of Seinfeld. One day, George and Jerry went to the bookstore. As Jerry searched for a book, George desperately needed to use the restroom. George loved to read on the toilet so he grabbed a book displayed on the shelves. Upon finishing his business and returning to Jerry, George was approached by a bookstore employee. The worker explained to George that the book he previously used in the bathroom was now flagged as a “bathroom book” and George had to purchase it. George refused to pay for the book, yelling that he had no use for it anymore. The worker calmly explained to George that the bookstore has a policy; if any books are used in the restroom, they will be flagged in the company’s database and not sold to anyone other than the person that contaminated it. Why do they have this policy? The book is no different than the one it is placed next to on the shelf? This Seinfeld scenario can be applied with any property, including Mel Acres Ranch. Once a piece of land, an article of clothing, or even a book become dirtied, or contaminated in some way, people simply don’t want to use them or pay as much for them. There is a reason you can buy a certain item for significantly less than another item that are made of the same material. Stigmas attach to property and affect the way buyers perceive them, which in turn, affect their value. These stigmas can be either positive or negative, but they are not temporary. Take guitars for example. Someone interested in buying a guitar could find a guitar priced for $1500 at the store. However, an identical guitar priced at $25,000 is also in the store. How is this possible? It turns out that the $1500 guitar is a regular guitar that’s sold to the store on a daily basis. The $25,000 guitar was played by world renowned artist Jimi Hendrix, thus explaining the huge disparity of price between the two guitars. This large disparity is representative of a positive and permanent stigma attached to the perception of a famous guitar. Stigmas attach to perception, which may or may not have an actual and real effect on the sale of an asset. The Supreme Court will have to answer the question whether or not a negative stigma is an element of damage calculations, and if so, allowing a jury to decide whether or not a potential stigma has an actual and real effect in any given case. Faulk Barchus is pleased to announce the submission of a brief on behalf of its clients in the 14th Court of Appeals in Houston, Texas. This brief was in response to a trial court order in our clients' favor which was appealed by the City of Houston. It wishes to recognize Sam Houston of Houston Dunn for his outstanding legal knowledge in Texas Civil Appellate Law and his help in Co-Authoring this brief. Houston Dunn is the go-to firm in Texas for an efficient and effective handling of your case as it travels through the appellate process.

The City of Houston drainage fee ordinance enacted in 2011 was enacted to provide additional revenue to provide drainage infrastructure and drainage services to "benefitted properties" located within the City of Houston. This is on top of the property taxes every property owner pays to the City of Houston every year.

There are many lots and parcels within the City of Houston that are not "benefitted properties", because they receive their drainage services from a municipal utility district, the Harris County Flood Control District, Harris County, the Army Corp of Engineers, and the Port of Houston Authority. Even though those property owners are required to pay for drainage improvements within Houston with a portion of their property taxes to the City of Houston and the HCFCD, those properties should not be required to pay the additional drainage charges and fees if they cannot use or benefit from the service Houston is unable to or cannot provide. Houston cannot use this fee as a disguised additional tax on every property owner within the city. The Rebuild Houston website has a page entitled "Why do I have to pay a drainage fee?", but it doesn't provide you with a straight answer. It basically says ...because we own some drainage and we already use 150 million of your tax dollars on drainage, but we still need more of your money. Faulk Barchus represents property owners in the Houston city limits who do not benefit from the city's drainage utility system, but rather drain into the bayous, or other facilities not owned or operated by Houston until it reaches the Gulf of Mexico. These property owners should NOT be assessed an additional drainage tax every month. Currently, Faulk Barchus represents clients who claim an exemption under the drainage fee ordinance, claim they have a wholly sufficient drainage system, claim they are not "benefitted properties" under the ordinance, claim the ordinance is invalid by state statutes Faulk Barchus believes that sometimes you have to get dirty to get results. "We don't believe in playing dirty in court, but we love to go the extra mile if it helps our clients get results,” said managing attorney Brandon Barchus. In preparation for a recent hearing against the City of Houston challenging the drainage fee charges against its clients, Barchus soaked himself with ditch water in his free time. Representing multiple clients and multiple properties in the case, it became difficult to remember the specific ditches, creeks and bayous that each properties’ drainage flowed. The legal title to these watercourses were also in dispute, and under Texas law the answers are sometimes contingent on the navigability of the streams and bayous. "It allowed us to gain a valued perspective on the case, and it helped us win. I certainly didn’t forget the facts during argument…or the distinct smell along the journey" Barchus said. In the legal world, a lot of times argument is based solely from what you see in the written evidence. Sometimes a case involves many fact issues and legal concepts, it can become overwhelming on paper. Challenging yourself to use your other senses gives you a whole new perspective on the purpose your client needed you in the first place. As lawyers, sometimes it is easy to pile documents on your desk and bury yourself in the minutia of the evidence. Viewing the evidence first hand allows you to visualize your arguments and articulate your facts in a way that makes it easier for others to understand. Even if you have to get dirty, your clients may thank you in the end. Faulk Barchus is pleased to announce its success in a winning argument against the City of Houston Wednesday establishing jurisdiction that our clients are not "benefitted properties", and therefore do not have to pay the drainage fees and charges, under the recently enacted City of Houston Ordinance. The clients' properties drainage does not flow through City of Houston maintained drainage infrastructure, but rather to Harris County Flood Control District, Special Municipal Utility District, and Harris County owned and operated drainage, then through the bayous and ultimately drains into the Houston Ship Channel or Clear Lake and into the Gulf of Mexico. The City of Houston and its attorneys have already filed a notice of appeal. Faulk Barchus attorneys maintained that the drainage fee is supposed to be relative to the City providing drainage service, and not a drainage tax. Therefore, if the City does not provide drainage services to your property, you should not have to pay a drainage fee. The Attached Flowchart was created by Faulk Barchus attorneys as a visual aid in explaining the complex legal concepts involved.

|

Oil and Gas Law Blog

Brandon M. Barchus Archives

June 2017

Categories

All

|

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed